Among its many criticisms of Nutrition North Canada (NNC), the auditor general’s report released late last November chastised Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) for failing to implement the cost containment strategy that was a Treasury Board condition for program approval. Senior officials from the department appeared at standing committee on public accounts on March 23, bobbing and weaving as they tried to defend the indefensible record of mismanagement of a program that promises to become a key election issue in as many as 10 northern ridings.

Just four days before the release of this report, the government announced additional funding for the program, amounting to $11.3 million in 2014-15 and $14.6 million in 2015-16. These amounts represent an increase of 24 per cent in the subsidies provided to retailers and wholesalers under this program, compared to what was planned when the program was implemented. For subsequent years, it was announced, the program would have a five per cent annual escalator. In fact, as AANDC’s Report on Plans and Priorities 2015-16 makes evident, the $14.6 million escalator for 2015-16 is “frozen,” subject to some undisclosed condition. And in 2016-17 and 2017-18, planned expenditures return to the same level as when NNC was implemented in April 2011.

In its response in the auditor general’s report, the department had the gall to say it would “continue [emphasis added] to apply cost containment in a manner that supports program objectives,” but “with a view to avoiding unintended price shocks and product shortages.”

Nutrition North Canada was announced in May 2010 as a $60 million per year program starting in 2011-12, consisting of $53.9 million for subsidy payments to food suppliers, $3.2 million for administration by AANDC and $2.9 million for Health Canada’s related nutrition education initiatives. Ever since, the media and the department have continued to refer to it as a $60 million program. It never was and never could be a $60 million program, if price shocks were to be avoided.

After greatly increasing the subsidy rates in October 2011, the minister was unwilling to roll them back in April 2012 to operate the program within budget in 2012-13 or the following year. Politically embarrassing price shocks would not be tolerated.

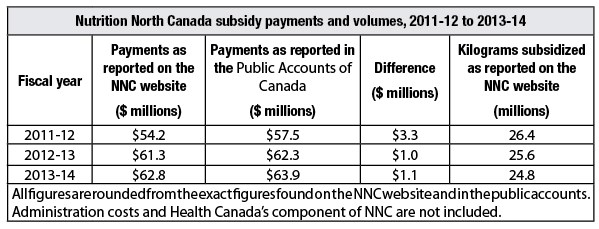

The subsidy figures provided on the Nutrition North Canada website, however, are millions of dollars less than the actual amounts as stated in the public accounts, which agree with the expenditure reported by the auditor general for 2012-13.

The differences between the two sets of figures are attributable to undisclosed amounts of payments made to food suppliers to cover transition costs during the first year of the program, as well as payments made on an ongoing basis to suppliers to cover their costs of submitting claims.

Since they are actually paid to prepare claims, it is hardly surprising that retailers such as the North West Company submit claims for the useless five cents per kg subsidy that is paid for shipping all eligible foods to communities eligible for a “partial subsidy” and for level 2 (“low subsidy”) foods shipped to some communities that are eligible for a “full subsidy” as well. The five cents subsidy, however, does serve the political purpose of producing inflated figures on volumes of subsidized shipments, which serve to make the program appear more successful than it really is.

Not included in either of these sets of figures are payments of another $1 million related to Nutrition North Canada in 2011-12 by the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency to assist certain businesses in making the transition.

In its 2013-14 departmental performance report, AANDC reported that it spent $66.2 million on Nutrition North Canada (stated to be $9 million more than planned), and attributed the difference to growth in demand for subsidized food, rather than to a failure to implement cost containment measures. But the volume of shipments actually decreased in 2013-14 according to the department’s own figures.

Not once before the announcement in November 2014 did the department disclose its real spending intentions, after it realized the consequences of operating within the $53.9 million budget cap. Year after year, money was quietly reallocated within the department. Even the 2013-14 departmental performance report stated “Nutrition North Canada operates with a capped budget.” That was the stated intention, but has never been the reality.

With the announcement last November, we thought that perhaps the Harper government had been the first to realize, finally, the absurdity of trying to operate a demand-driven food subsidy program intended to encourage the consumption of nutritious food within an expenditure cap which forces the department to take action that will increase the cost of these foods, thereby undermining the program’s objective. However, the previously undisclosed “frozen allotment” now suggests the escalator was nothing more than a short-term decision intended to get the government past the next election.

On the other hand, the additional funding and escalator announced will not be sufficient to address the inequitable treatment of communities currently eligible for a full subsidy, a useless, partial subsidy or no subsidy at all, that began with the replacement of the Food Mail Program with Nutrition North Canada in 2011. In fact, equitable treatment is not even possible under the new program structure, for reasons that are beyond the scope of this article.

Fred Hill managed the Food Mail Program in different capacities at Indian and Northern Affairs Canada from 1991 until 2010, in collaboration with Michael Fitzgerald between 2008 and 2010.