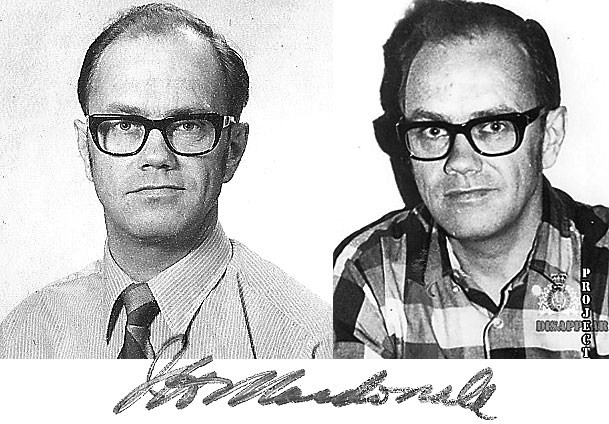

Forty-one years ago today, James (Jim) Hugh Macdonald, 46, the owner of J.H. Macdonald & Associates Ltd., consulting structural engineers on Pembina Highway in Winnipeg, climbed into his Mooney Mark M20D single-engine prop aircraft, bearing the registration mark CF-ABT, and took off half an hour after sunset from Thompson Airport at 4:30 p.m. to make his return flight home and disappeared into the rapidly darkening sky to never be seen or heard from again. He was the sole occupant of the four-seater plane.

With the disappearance, Macdonald, born and raised in Winnipeg and only up here on a day's business, instantly became Thompson's most famous missing persons case.

To this day, the Winnipeg private pilot and civil engineer, who would be 87 if he were still alive today, is still listed by the RCMP as a "missing person," as no remains or wreckage were ever found, and is featured on the website of "Project Disappear," Manitoba's missing person/cold case project managed by the RCMP "D" Division historical case and major case management units in Winnipeg at: http://www.macp.mb.ca/results.php?id=r1065. "The file is currently still under investigation and is with the RCMP "D" Division historical case unit," Sgt. Line Karpish, senior media relations spokesperson for the Mounties in Winnipeg, said Dec. 6.

Claire Macdonald told the Nickel Belt News in her first ever interview on her husband's disappearance by telephone from Winnipeg Dec. 5. that J.H. Macdonald & Associates Ltd. was a small firm, she said, with about seven employees. Jim Macdonald was the only professional engineer on staff and a few months after his disappearance, its business affairs were wound down.

One of Macdonald's last projects as a consulting structural engineer was the construction of additional classroom space for special needs students at Prince Charles School on Wellington Avenue at Wall Street in Winnipeg.

Claire Macdonald says she knows her husband was in Thompson on business the day his plane disappeared, but is not sure exactly what the business was. It may or may not have been related to proposed work for the School District of Mystery Lake, she says, since school construction projects were one of his areas of expertise. "He was just on a one-day trip to check out some work he was coming back that night." Macdonald, who graduated from the University of Manitoba with his civil engineering degree in 1950, often worked with architectural firms, including his brother's, she added. Other than working for a year in Saskatoon, he spent his entire career living and working in Winnipeg, Claire said.

Macdonald, who was born on March 20, 1925, trained as a pilot when he was 19 and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) shortly before the Second World War ended in 1945 and before he could be shipped overseas into the theatre of combat operations. Claire, also born and raised in Winnipeg, met James Hugh Macdonald, who went by the name of Jim, through friends in 1947, she says, and they were married in 1950, shortly after he graduated from university. She never remarried after Jim Macdonald's plane disappeared in 1971.

The couple had two children, the oldest, a daughter, Joan, who today is a librarian with the Pembina Trails School Division in the Fort Garry area of Winnipeg, and her younger brother, Bill, a teacher and freelance journalist, and noted author in 1998 of The True Intrepid: Sir William Stephenson and the Unknown Agents. Stephenson was the famous, or infamous, depending on your historical take, British Security Coordination (BSC) spymaster - codename Intrepid - set up by British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). Ian Fleming, the English naval intelligence officer and author, best known for his James Bond series of spy novels, once said of his friend Stephenson, a Winnipeg native: "James Bond is a highly romanticized version of a true spy. The real thing is ... William Stephenson."

"Actually I always wanted to be a detective Instead I became a curious librarian!" Joan Macdonald said in a Dec. 5 e-mail.

At the time Jim Macdonald's plane disappeared, Joan was 17 and Bill 15, old enough to remember their dad, Claire said. "Oh, absolutely, I was glad they had him that long." They lived on Fletcher Crescent in the Fort Garry area of Winnipeg. "In the late Forties he had been a pilot. Then he took it up again," Claire said. "He hadn't had his plane long" at the time of the trip to Thompson, she said. "He was gung-ho to go. I suggested maybe he could take the commercial flight and his reply was, 'I want to live,'" meaning to experience life to the fullest, said Claire.

That was very much in keeping with who Jim Macdonald was. An avid outdoorsman, who loved skiing in the winter and boating in the summer, he was also a photographer who developed his own film and made prints in his darkroom. As well, Macdonald was also active with Fort Garry United Church on Point Road in Winnipeg and used to take old magazines into Norway House with him when he flew up there because he knew local residents didn't have a lot of reading material to choose from in the early 1970s, Claire recalled. "He was aware of how little they had he was a kind person."

"He was very passionate about flying," Claire said. "And he'd been very active with the Winnipeg Gliding Club, too." After the aviator went missing, the family had a memorial bench placed in Crescent Drive Park in Winnipeg to honour Jim Macdonald's memory. The inscription on the plaque reads, "His spirit soars."

Claire Macdonald jokes she was never as enthusiastic about flying as her husband. "I say I flew with him before we were married and not after," she laughs. "I'm not keen on flying. I don't need that thrill."

From the disappearance of Amelia Earhart in 1937 through the disappearance of Flight 19, the five United States Navy TBM Avenger Torpedo Bombers that went missing over the Bermuda Triangle in the Atlantic Ocean on Dec. 5, 1945, there had long been a huge public fascination with the mystery of missing aviators before Macdonald disappeared.

While no one really thought Jim Macdonald went intentionally missing, Claire Macdonald said someone once wildly jokingly said to her, "Maybe he flew to Mexico." Claire observed Wednesday: "How far can you go in that little plane in that winter weather?"

Macdonald had filed a 3 1/2 -hour flight plan to fly Visual Flight Rules (VFR) via Grand Rapids to Winnipeg that Tuesday. It was around -30 C at the time of takeoff on Dec. 7, 1971 and the winds were light from the west at five km/h, according to Environment Canada weather records, said Dale Marciski, a meteorologist with the Meteorological Service of Canada in Winnipeg. Macdonald was reportedly wearing a brown suit jacket when he took off from Thompson and it was unknown whether the plane was carrying winter survival clothing and gear.

While there was some ice fog, Marciski said, the sky was mainly clear and visibility was good at 24 kilometres. Transport Canada's VFRs for night flying generally call for aircraft flying in uncontrolled airspace to be at least 1,000 feet above ground with a minimum of three miles visibility and the plane's distance from cloud to be at least 2,000 feet horizontally and 500 feet vertically. Transport Canada investigated the disappearance of Macdonald's flight in 1971 because the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) had yet to be created.

Macdonald's disappearance trigged an intensive air search that at its peak in the days immediately after the aviator went missing involved more than 100 personnel covering almost 20,000 miles in nine search and rescue planes from Canadian Armed Forces bases in Edmonton and Winnipeg, including a Lockheed T-33 T-bird jet trainer and two de Havilland short takeoff and landing CC-138 Twin Otters, two RCMP planes and 11 civilian aircraft. "It was a huge search," Claire Macdonald said. "Remarkable ... there was a huge effort and then nothing came of it."

The search for Macdonald and his Mooney Mark M20D began only hours after his disappearance, on the Tuesday night. The Lockheed T-33 T-bird jet trainer flew the missing aircraft's intended flight line from Winnipeg to Thompson and back to Winnipeg, Capt. Dale Alleman, a pilot involved in flying the search from 440 Transport and Rescue Squadron at Canadian Forces Base Edmonton, told the Thompson Citizen in 1971. The T-33 carried highly sophisticated electronic equipment and flew Macdonald's flight plan both ways at extremely high altitude hoping to pick up signals from the Mooney Mark M20D's emergency radio frequency, or the crash position indicator, a radio beacon designed to be ejected from an aircraft if it crashes to help ensure it survives the crash and any post-crash fire or sinking, allowing it to broadcast a homing signal to search and rescue aircraft, which was believed be carried by Macdonald on the Mooney Mark M20D, said Alleman.

The next morning - Dec. 8, 1971 - search and rescue aircraft re-flew the "track" in a visual search both ways, assisted by electronic listening devices, to no avail.

The area between Winnipeg and Thompson on both sides of the intended flight pattern was then zoned off and aircraft were assigned to particular zones and then flew the zones from east to west at one mile intervals until the entire area was over flown - first at higher altitudes and then again at lower altitudes.

Every private or commercial pilot flying the area assisted the organized search, Alleman said. Thompson Airport's central tower was issuing a missing plane report at the end of every transmission, asking pilots in the area to keep a visual watch for Macdonald's aircraft, and to listen for transmissions on the emergency band on their radios.

A second search for Macdonald and his Mooney Mark M20D single-engine prop aircraft was commenced almost six months later in May 1972, after spring had arrived in Northern Manitoba and all the snow had melted. Nothing turned up.

Every Dec. 7, for many years after Jim Macdonald's disappearance, the immediate family - Claire, Joan and Bill - would gather quietly for dinner in Winnipeg, just the three of them, to remember a husband and father.