Ian Mosby, a historian of food and nutrition and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) postdoctoral fellow at the University of Guelph, has recently published an academic paper on how hungry aboriginal children and adults were used between 1942 and 1952 as unwitting subjects in nutritional experiments by federal government scientists and bureaucrats.

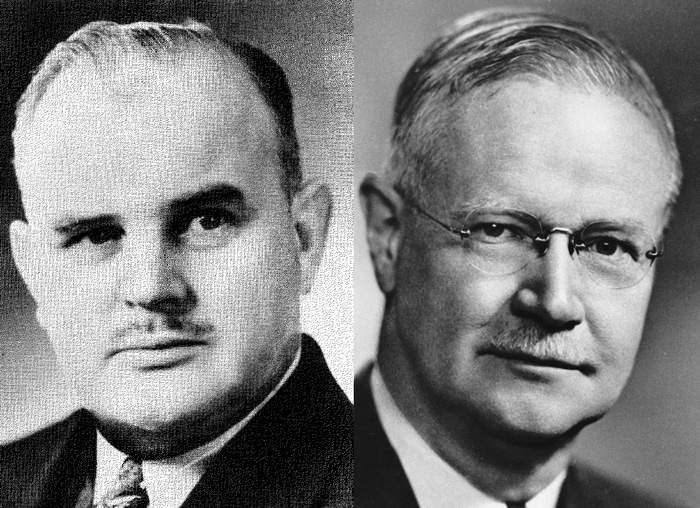

It began with a March 1942 visit spearheaded by Dr. Percy Elmer (P.E.) Moore, superintendent of Medical Services for Indian Affairs, and RCAF Wing Commander Dr. Frederick Tisdall - Canada's leading nutrition expert and the co-inventor of the infant food Pablum - a group of scientific and medical researchers travelled by bush plane and dog sled to a number of remote Cree communities in Northern Manitoba, including Cross Lake, Gods Lake Mine, Rossville, The Pas and Norway House. Moore had received his Doctor of Medicine degree from from the University of Manitoba in 1931 and upon graduation took a position as medical superintendent of the Fisher River Indian Agency in Hodgson.

Researchers found aboriginal Cree who were hungry, impecunious and necessitous, due to a combination of the collapsing fur trade and declining government support. "It is not unlikely that many characteristics, such as shiftlessness, indolence, improvidence and inertia, so long regarded as inherent or hereditary traits in the Indian race may, at the root, be really the manifestations of malnutrition," the researchers concluded in a preliminary report on their study in March 1942. "Furthermore, it is highly probable that their great susceptibility to many diseases, paramount amongst which is tuberculosis, may be directly attributable to their high degree of malnutrition arising from lack of proper foods."

At the time in 1942, aboriginals in Manitoba had an infant mortality rate eight times that of the rest of Canada, and a crude mortality rate almost five times that of Manitoba as a whole, the researchers wrote in March 1946 in their study "Medical Survey of Nutrition Among the Northern Manitoba Indians," published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

At the Assembly of First Nations annual meeting in Whitehorse July 18, Canada's largest aboriginal group passed an emergency resolution calling on the Harper government to apologize for the experiments conducted between 1942 and 1952 on 1,300 people.

Federal government officials have said Prime Minister Stephen Harper's 2008 apology for the harm done by residential schools was intended to cover all wrongdoing against aboriginals. But chiefs at the meeting said that was not good enough.

"The chiefs-in-assembly will not accept the apology as catch-all recognition for all federal policy past, present and ongoing which have and continue to negatively impact aboriginal peoples," the draft of the resolution stated.

It also demands the government release all records pertaining to any other tests on aboriginal people.

The chiefs-in-assembly also called on the federal government to work immediately to provide the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission full and complete access to all records held by the federal government on experiments conducted on aboriginal communities and aboriginal children in residential schools.

The first experiment began in 1942 on 300 malnourished Cree at Norway House. Of that group, 125 were selected to receive vitamin supplements, which were withheld from the rest. At the time, researchers calculated the local people were living on less than 1,500 calories a day. Normal, healthy adults generally require at least 2,000. Dr. Cameron Corrigan, the resident physician for the Indian Affairs Branch at Rossville, conducted most of the experiments.

By 1947 plans were developed for research on about 1,000 hungry aboriginal children in six residential schools in Port Alberni, B.C.; Kenora, Ont.; Shubenacadie, N.S.; and Lethbridge, Alta. By 1952, at least 1,300 aboriginals had been studied, most of them children.

Mosby's paper, "Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools, 1942-1952," appears in the May issue of the scholarly journal, Histoire sociale/Social History. Little has been written about the nutritional experiments. A May 2000 article by David Napier in the Anglican Journal about some of them was the only reference Mosby could find.

"This is a period of scientific uncertainty around nutrition," Mosby is quoted as saying in a July 16 Canadian Press story by Bob Weber. "Vitamins and minerals had really only been discovered during the interwar period.

"In the 1940s, there were a lot of questions about what are human requirements for vitamins. Malnourished aboriginal people became viewed as possible means of testing these theories." The Canadian Council on Nutrition (CCN), an advisory body made up of the nation's leading nutrition experts, been formed in 1938, and the Nutrition Services Division of the Department of Pensions and National Health was created in 1941.

Mosby notes on his webpage, "This is the first piece of new, non-dissertation related research I've published since receiving my PhD and it was, without a doubt, the most difficult research project I've undertaken. But while the subject matter and the sources were often disturbing, I think that the story itself is one the needs to be told if Canadians hope to come to grips with the devastating impact of Canada's colonial policies governing the lives of aboriginal peoples.

"Between 1942 and 1952, some of Canada's leading nutrition experts, in cooperation with various federal departments, conducted an unprecedented series of nutritional studies of Aboriginal communities and residential schools. The most ambitious and perhaps best known of these was the 1947-1948 'James Bay Survey of the Attawapiskat and Rupert's House Cree First Nations.' Less well known were two separate long-term studies that went so far as to include controlled experiments conducted, apparently without the subjects' informed consent or knowledge, on malnourished aboriginal populations in Northern Manitoba and, later, in six Indian residential schools.

Little appears to have been learned from the decade-long research from 1942 to 1952, Mosby said. While a few academic papers were published, he said couldn't find evidence that the Norway House research program was completed.

"This article explores these studies and experiments, in part to provide a narrative record of a largely unexamined episode of exploitation and neglect by the Canadian government. At the same time, it situates these studies within the context of broader federal policies governing the lives of Aboriginal peoples, a shifting Canadian consensus concerning the science of nutrition, and changing attitudes towards the ethics of biomedical experimentation on human beings during a period that encompassed, among other things, the establishment of the Nuremberg Code of experimental research ethics.

"In doing so, this article argues that - during the war and early postwar period - bureaucrats, doctors, and scientists recognized the problems of hunger and malnutrition, yet increasingly came to view aboriginal bodies as 'experimental materials' and residential schools and aboriginal communities as kinds of 'laboratories' that they could use to pursue a number of different political and professional interests. Nutrition experts, for their part, were provided with the rare opportunity to observe the effects of nutritional interventions (and non-interventions, as it turned out) on human subjects while, for Moore and others within the Indian Affairs and Indian Health Services bureaucracy, nutrition offered a new explanation for - and novel solutions to - the so-called 'Indian Problems' of susceptibility to disease and economic dependency. In the end, these studies did little to alter the structural conditions that led to malnutrition and hunger in the first place and, as a result, did more to bolster the career ambitions of the researchers than to improve the health of those identified as being malnourished."

"The research team was well aware that these vitamin supplements only addressed a small part of the problem," Mosby writes. "The experiment seems to have been driven, at least in part, by the nutrition experts' desire to test their theories on a ready-made 'laboratory' populated with already malnourished human experimental subjects."

One school deliberately held milk rations for two years to less than half the recommended amount to get a 'baseline' reading for when the allowance was increased. At another, children were divided into one group that received vitamin, iron and iodine supplements and one that didn't.

One school depressed levels of vitamin B1 to create another baseline before levels were boosted. A special enriched flour that couldn't legally be sold elsewhere in Canada under food adulteration laws was used on children at another school.

And, so that all the results could be properly measured, one school was allowed none of those supplements.

Many dental services were withdrawn from participating schools during that time. Gum health was an important measuring tool for scientists and they didn't want treatments on children's teeth distorting results.